This post first appeared on the SANDSWA blog on March 7, 2023.

Last November, coincidentally a couple of days after Twitter was sold to Elon Musk, the San Diego Science Writers Association (SANDSWA) met in a local brewery and the question came up: should we stay on Twitter or should we go? If we do leave, where would we go? We didn’t delve into alternatives but it kept nagging me.

Mastodon had already been on my radar—first as a little child when I saw beautiful illustrations of the extinct Mammoth species by Czech illustrator Zdeněk Burian, and later, in 2017, when I learned about the alternative microblogging service named after this creature on the German technology news site Heise. I had already signed up some time ago, but I was using an alias and I wasn’t even posting, just like how I started on the bird site. About a week after our meeting at the brewery I decided to use Mastodon and finally made a new account with my real name. Why?

Then and now

During the information age, human communication has changed drastically. While the widespread access to phone calls still somewhat mimicked a natural one-to-one conversation and old broadcast radio and TV are not more than multimedia newspapers, human communication has taken a wild turn with the birth of online message boards, the universal acceptance of emails and messenger apps, the world wide web and its rise of home pages, blogs, and finally social media.

Now, on top of interactions “in real life”, we have networks of interacting utterings in text, image, and sound. Exchanges between friends, acquaintances, and strangers: approval and disapproval, facts and lies, fun and stress, enlightenment and obfuscation, love and hate. Information exchange–anywhere, anytime, on devices that accompany most of us every day.

Many smart things have been said about how social media affects our lives. But when one rich person bought one big chunk of this multilayered network and immediately started to change its rules, more people than ever began to contemplate the use, function, and consequences of our current networks of human interactions.

Who is in control?

I see two different ways these networks are controlled: they are either in the hand of the users or of someone else, with additional interests attached. The interests are usually financial and by extension of power.

In chat groups of friends it is the friends who chose the members and agree on the tone of conversation. Even in the one-sided communication of a newsletter it is only the writer who gets to decide what to post and what it looks like, to whom and when it is delivered.

On commercial platforms it is different: a bunch of rich people and/or a revenue-driven company decides who can sign up, who moderates, whether you can put a nipple in your profile pic and which message is shown to you when. The design is shaped by the interests of the owners, it is streamlined to maximize the owner’s benefits, and the algorithms are company secrets.

It might be worth it. It might be faster and have bigger storage or other features. Maybe it looks better and is less rough around the edges. But it takes your information hostage. By tweeting for example, you grant Twitter a license to –let that sink in– “use, copy, reproduce, process, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute such Content.” The content being your own creation. The rules of YouTube and Facebook read similarly.

Many eggs, in one basket?

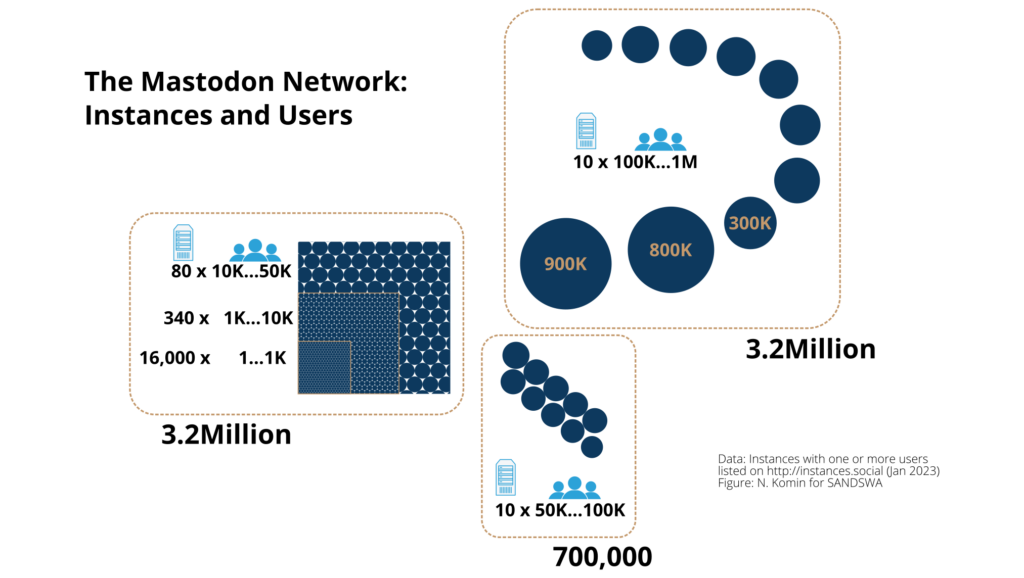

The Twitter alternative Mastodon currently counts about seven million users, give or take. It is little compared to the big commercial networks, but all these users call one of nearly twenty thousand different “instances” their digital home. “Instances” are servers maintained by one or a few individuals. A bit more than a tenth of the users distributes over 99% of all servers, while the largest server provides service to another tenth.

Now, all these admins have full control over and insight into account data. But so have the revenue-driven companies that own the commercial networks. One leaked database and the privacy of millions could be jeopardized. One decision in the central management and millions could become part of a scientific experiment, users might suddenly be required to use their real name, or their posts might be denied if rules around content changes.

Sure, even the developers of an open-source software with open interfaces could theoretically close access to third-party applications or disallow links to alternate platforms–why would they though? But the distributed structure of Mastodon requires the cooperation of all (or a majority of) the admins for a new feature to be adopted. What might feel to some as a hindrance to progress, to others is reliability.

They say, there is no free lunch

The costs of our communication need to be covered. Most people are aware that on a free platform, the user is the product. And it goes beyond targeted advertisements. Your content will be analyzed to serve the network owner and to alter underlying algorithms. It can and will be fed into databases to train AI for text or image generation and face and voice recognition.

Mastodon instances are based on donations or a sponsoring institution. The European Union’s Data Protection Supervisor and the German Government, not commonly regarded as digital avant-garde, went ahead and opened their instances. It’s an easy way to prevent impostors and maintain brand care. It also fosters independence from third parties with adverse intentions. Any organization, be it governmental or economic, educational or research, that relies on public interaction should follow suit and take control of its communication infrastructure—an unquestioned fact in the case of email servers.

So, stay or go?

Why not both? I still have my bird account but see myself less and less opening the app, posting more seldom than ever. My last tweet linked to the news article “Elon Musk’s Twitter blocked links to rival Mastodon.” It reads like something you can’t make up. After that, I just couldn’t bring myself to feed that platform with my content anymore.

Currently, many more people are flying with the bird than riding on the Mammoth. Many are afraid to lose their reach by switching, but that cannot change unless the collective makes the move. The more content we feed, the greener become the fields to graze.